The Buran spacecraft left an indelible mark in people’s hearts and a feeling of bitterness, disappointment and dissatisfaction that the Energia-Buran programme was stopped at the very beginning of its journey. The event that took place 35 years ago remains one of the most impressive achievements in the history of both national and world cosmonautics, despite the fact that Buran made only one flight.

On that day, 15 November 1988, the ship circled the globe twice in 205 minutes. The flight was performed in unmanned, fully automatic mode, and its landing on the 4.5-kilometre runway of the Yubileyny airfield at Baikonur Cosmodrome was the most impressive moment.

30 minutes before the engines were started, the commander of the Energia-Buran launch team, Vladimir Gudilin, received a storm warning about fog and visibility of 600-1000 m, south-west wind of 9-12 m/sec, with gusts up to 20 m/sec. After a brief meeting, having changed the direction of the Buran landing, the management decided to launch the spacecraft, which passed without any remarks.

At the 482nd second of the flight the spacecraft entered the calculated orbit. In the hall there was traditionally no noise, neither exclamations nor applause. In accordance with the strict instruction of Boris Gubanov, the chief designer of the Energia launch vehicle, all those present at the command centre remained at their workplaces.

Three and a half minutes later, Buran, being in the “lying on its back” position, issued the first 67-second correction pulse and, having received an incremental orbital velocity of 66.7 m/sec, moved to an intermediate orbit. While waiting for the next pulse, the ship continued to fly in the “inverted” position and after the second 40-second pulse entered the working orbit with a height of 263-251 km, inclination of 51.64° and an orbital period of 89 minutes 27 seconds. To ensure optimal thermal conditions, the spacecraft flew with the left wing turned towards the Earth – the sun’s rays in this orientation heated mainly the lower refractory surface of the wing and fuselage.

All systems in flight in orbit worked normally. Four communication sessions were conducted, including the transmission of information necessary for descent and landing, including the wind direction in the runway area of Baikonur Cosmodrome. At the 67th minute of the flight, outside the radio communication zone, Buran began to prepare for landing. From the magnetic tape of the on-board tape recorder, the RAM of the on-board computer system was reloaded to work on the descent section, and the pumping of fuel from the nose tanks to the aft tanks began to ensure the required landing alignment. Preparation, orbital descent, re-entry into the upper atmosphere and exit from the plasma cloud also proceeded normally.

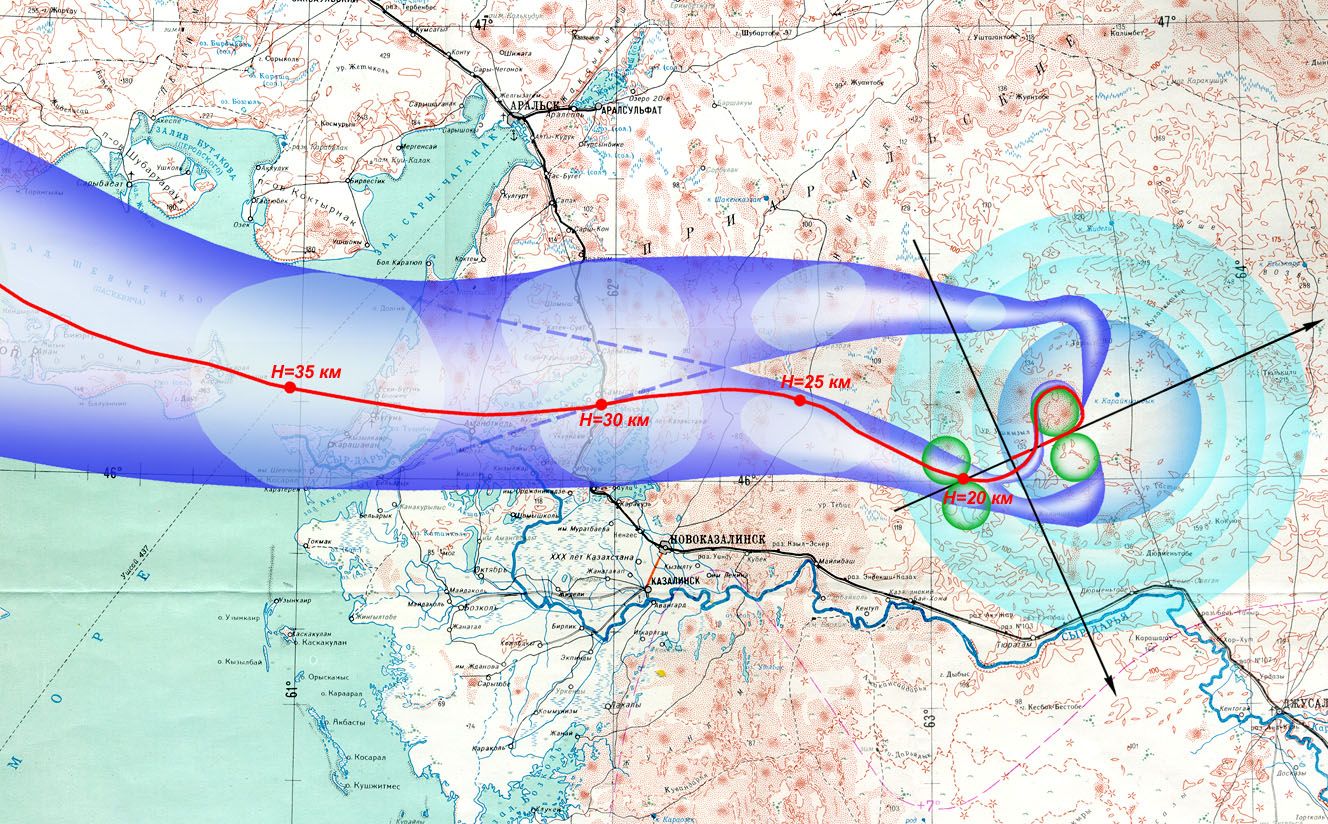

In the area of the Yubileyny aerodrome, a strong gusty wind with a speed of 15 m/sec and gusts up to 18-20 m/sec was still blowing almost along the landing strip. Clarified speed and direction were transmitted to the ship before the braking impulse was issued, and this data for the onboard computer complex unambiguously determined that the landing approach should be made from the north-eastern direction to runway No. 26.

So far the flight had been strictly following the calculated descent trajectory. The ship was approaching the aerodrome slightly to the right of the landing strip axis, and everything was going to be in favour of a landing approach from the southern course reference cylinder (CRC). However, when entering the key point from an altitude of 20 km, from which begins the pre-landing manoeuvring, “Buran” performed a turn that shocked everyone in the room. Instead of the expected landing approach from the southeast with a left turn, the ship energetically turned to the left, to the northern CRC, at an altitude of 11 km passed over the runway and began to approach from the northeast direction with a right turn.

Post-flight analysis showed that the probability of choosing such a trajectory was less than three per cent, but in the weather conditions that prevailed in the runway area of the cosmodrome, it was the most correct decision of the ship’s onboard automatic control system.

At an altitude of four kilometres “Buran” entered a steep landing glide path with a descent rate of 40 metres per second. Continuing to rapidly approaching the runway with the released landing gear, it begins to first level off and then raise the nose, increasing the angle of attack and creating an air cushion under itself. The vertical speed 10 seconds before touchdown was already 8 m/s. For a moment the ship hovered over the concrete surface and made such a soft landing that at the moment of touchdown the shock absorbers were not fully compressed to the parking position and the brake parachutes were released only after 9.2 seconds.

The runway touchdown occurred 190 metres short of the design point, the lateral deviation to the right of the runway axis was 9.4 m, and the vertical speed of the touchdown was 0.3 m/s. During the run, already after touchdown, the ship control system continued to “search” for the runway centreline, trotting the front landing gear strut and selecting a minor lateral miss due to drifting by the headwind. As a result, at a distance of 1620 m from the touchdown point the spacecraft stopped with a 5.8 m deviation to the left from the runway axis.

The Energia-Buran programme was the Soviet Union’s response to the challenge posed by the USA with its Space Shuttle programme. The Buran orbiter was designed to control near-Earth space, return satellites and perform other tasks. As it happens, space is considered the technological showcase of the world. The successful flight and brilliant landing of the 80-ton ship in fully automatic mode allowed people not only involved in the programme, but also the whole country to feel an unusually acute sense of national pride and joy for their country, for the powerful intellectual potential of our people. It was not just revenge for the (“lost”?) lunar race, for the seven-year delay in launching a reusable spacecraft – it was our real triumph.